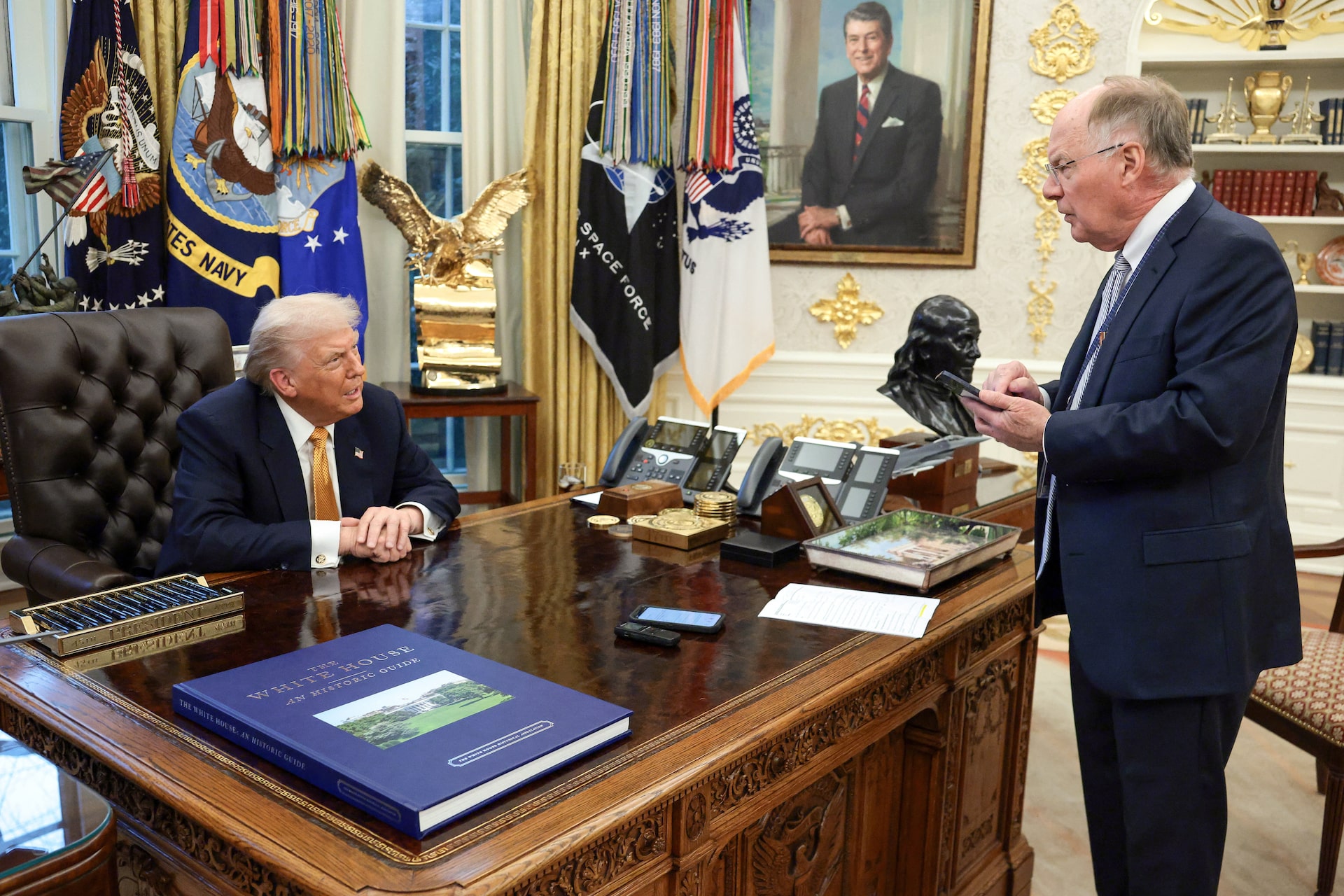

Newlywed couples pose for pictures at the Huguo Guanyin Temple, an outdoor marriage registration site in Beijing, China, October 28, 2025. REUTERS

SINGAPORE/BEIJING, Nov 7 (Reuters) – When bank clerk Ren Yingxiao was looking for a honeymoon destination with her partner, they came across a scenic spot in the Xinjiang region that had it all – including a marriage registration office.

“So we thought, why not go there and get our marriage certificate as well?” the 30-year-old said about secluded Sayram Lake, where authorities are trying to attract young Chinese to tie the knot as part of a nationwide push to boost marriage rates and ease the country’s demographic crisis.

In May, China started allowing couples to get married anywhere in the country – instead of their place of residence – making the process more convenient and the event more special.

Local governments have since started to scramble for marriage tourists, setting up registration offices around scenic spots, at music festivals – and even in subway stations, shopping malls and parks.

CHINA’S MARRIAGE RATES RISE

For now, the effort is working.

Marriages, which demographers use as a proxy for the country’s birth rate, rose 22.5% from a year earlier to 1.61 million in the third quarter of 2025, putting China on track to halt a downtrend in annual nuptials, which has gone almost uninterrupted for more than a decade.

Last year’s 20.5% decline in marriages, to 6.1 million, was the biggest on record.

In the eastern city of Nanjing, couples can get married at the Confucius Temple, where they can have a Ming Dynasty-themed ceremony. In southwestern Chengdu, authorities set up an office on the picturesque Xiling Snow Mountain at an altitude above 3,000 metres (9,842 feet). In eastern Hefei, a marriage booth opened in a subway station whose name, Xingfuba, translates to “the place of happiness.”

And in Shanghai, couples can choose to get their certificate at a nightclub after appearing at a marriage registration office, thanks to a partnership between INS Park, a six-storey nightlife complex, and the Huangpu District Civil Affairs Bureau.

In Beijing, 31-year-old lawyer Wang Jieyi and 33-year-old Zhan Yongqiang, a bank employee, registered their marriage at the Huguo Guanyin Temple.

“The Huguo Guanyin Temple was originally built to safeguard the peace and tranquility of the nation,” Wang said. “And also, in our traditional religious culture, the Guanyin Temple is associated with auspicious events like marriage and giving birth, symbolising happiness and well-being.”

The couple said the new policy didn’t necessarily fast-track their plans to get married but it made the process more convenient as they both work in Beijing and no longer need to go back to their native Shandong province.

“It made our lives a little bit easier,” said Wang.

IT’S A NUMBERS GAME

Tourists go to Xinjiang’s Sayram Lake, where Ren got married, for the steep mountains and quiet pastures surrounding it. But it’s the lake’s geographical statistics that convince couples to marry there.

It stands 2,073 metres above sea level, a number that sounds like “love you deeply” in Chinese. It has a surface area of 1,314 square kilometres and that figure is phonetically similar to “a lifetime.” Xinjiang’s capital, Urumqi, is 520 kilometres away – homophonous with “I love you.”

“All those numbers had symbolic meaning,” said Ren.

Demographer Yi Fuxian from the University of Wisconsin-Madison said the removal of geographic restrictions is making weddings easier in China, but expects the positive results to be “short-lived.”

With the population declining, Yi expects the number of women aged 20 to 34 to nearly halve to 58 million by 2050. Moreover, he expects young women – and their parents – to give greater priority to education and economic independence over marriage, in line with global trends.

Ren concurred, saying she would have gotten married anyway. She believes marriage and birth rates will improve only when incomes start growing and people feel more financially secure.

“It’s unlikely that two people who didn’t plan to get married would suddenly decide to do it on impulse while travelling,” she said. “That’s not very realistic.”

Reporting by Claire Fu in Singapore and Josh Arslan and Tingshu Wang in Beijing; Editing by Marius Zaharia and Thomas Derpinghaus